Recent Articles

- Weekly Roundup, December 19th June 25, 2015

- Weekly Roundup, December 12th June 25, 2015

- Weekly Roundup, November 28th June 25, 2015

by Donna R. Gabaccia, Professor of History, University of Minnesota

Family stories are important in immigration debates and in the National Dialogues on Immigration. They remind us how closely policy is entwined with personal history. Even in a “nation of immigrants,” however, many may feel they have no personal stories to share. There are no “immigrants” in many American family trees.

Is your definition of “immigrant” capacious enough, for example, to include the story of my great-grandfather who he left his tiny village in northwestern Italy for New York City but returned to Italy in 1892, after his first wife died? Perhaps not.

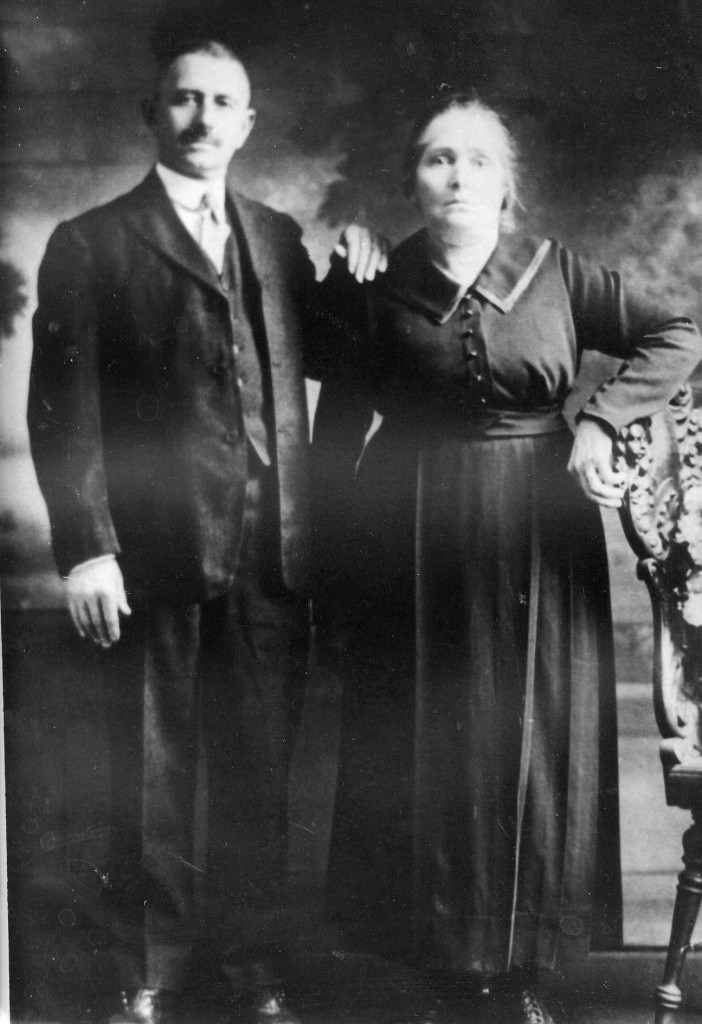

Antonio and Felicita Gabaccia, circa 1912 (before his second, and final, journey to for the United States)

You might feel more comfortable including him immigration history when you learn he made a second trip to New York in 1912, this time with his second wife–they are shown in the picture below–and died in Manhattan in 1918. My great-grandmother complicated the story further by immediately returning to Italy.

Would you label as an immigrant the baseball player Alex Rodriguez, who was born in New York City—and thus a citizen–but who returned at age four to the Dominican Republic with his parents? (The family later relocated to Miami.)

And what about Eric Ripert, the chef and part-owner of New York’s Le Bernardin, who was born a French citizen in Antibes but who has lived in the United States since 1989? Many Americans today might label the prosperous Ripert as an “expatriate,” or “expat”–the same word they use to describe the many U.S. citizen businessmen and intellectuals who go abroad to work–a move that is part of my own personal story.

Is an international student an immigrant? A temporary worker? A refugee? Although I can’t guarantee readers will find its distinctions convincing, here is a Website that promises to teach readers how to distinguish an immigrant from a refugee.

The point I am making is that language is changeable, and so is the meaning of the word immigrant. Before 1800, few English-speakers anywhere even used the word. Historical images of Castle Garden—a processing station in New York Harbor before Ellis Island—show that it was called an “Emigrant Landing Depot” and reveal its door marked as “Entry—For Emigrants Only.” New York State’s “Commissioner of Emigration” operated the facility.

For much of the nineteenth century, Americans called foreigners entering their country “emigrants” rather than “immigrants,” a pattern confirmed by a Google NGram.

The “emigrant” was presumed to be an pioneer heading westward as settler and colonizer of the frontier. Immigrant” was used mainly for those who would work for wages. Much historical evidence suggests that the word immigrant was a pejorative term in the 1890s and most often used to label the Chinese, on the west coast, and the Italians, on the East Coast.

The malleability of language has consequences. Consider the sharp, recent rise in the use of the terms “illegal alien” and “illegal immigrant–also documented here by a Google NGgram. These words symbolically exclude many recent migrants from the “Nation of Immigrants.”

Sizeable numbers of Americans already sense that exclusion and do not view their family stories as part of America’s immigration history. The family histories of the first Americans (Native Americans) provide the most obvious example. Americans who include in their family trees either asylum-seeking Pilgrims or slaves forced through the Middle Passage rarely consider themselves descendants of immigrants. Hispanics in the American southwest can even safely claim their families crossed no border—on the contrary, “the border crossed them” (as a result of the 1848 U.S. war with Mexico).

Yet all these Americans—along with the many Puerto Ricans who arrived in the United States in the twentieth century as citizens—led mobile lives. Their family histories, like those of the immigrants, document travel over very long distances; many also feature daunting periods of cultural change and changing identities or include memories of sharp racial, religious, and ethnic conflict. The African-Americans of the “Great Migration” from the rural south to the urban north and west were also as motivated by a search for freedom and new economic opportunities as were immigrants from Asia, Mexico or Europe.

One of the major challenges of using family stories to personalize immigration debates is finding ways to hear and to include the stories of Americans who fall outside the ever-changing boundaries and definitions of the word “immigrant.” Yet their voices, too, need to be heard in the National Dialogues on Immigration.